One of the most stark and tangible aspects of life in poverty is that of hunger. Without enough resources, parents are often not able to provide food for themselves or their children. Lack of food, or lack of nutritious food, can lead in turn to poor health, including birth defects for babies of pregnant mothers, under development of cognitive function in young children, and lower immune function which increases chances of catching disease. In short, food affects almost all areas of life: education, productivity and work, and the psychological stress of worrying about when the next meal may be.

The United Nation’s second Sustainable Development Goal (SDG), is Zero Hunger, specifically, to “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.” The Philippine government highlighted achieving zero hunger by 2028 as a key goal for the incoming administration during the launch of the Food Stamp Program in 2023.

Yet food insecurity, meaning skipping meals, running out of food, or not eating enough, is rampant throughout the populations ICM serves in the Philippines.

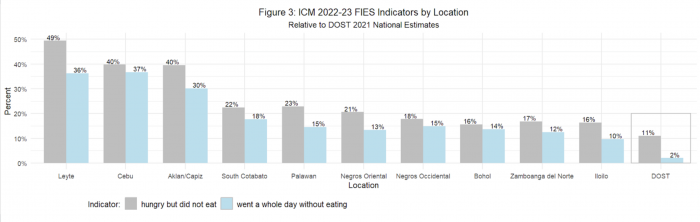

Within the Philippines, the Department of Science and Technology estimates 2% of the national population as being severely food insecure. But ICM’s surveys from 2021-23 show a much greater need, with 12.7% of the families we serve being severely food insecure and 37.9% being moderately or severely insecure.

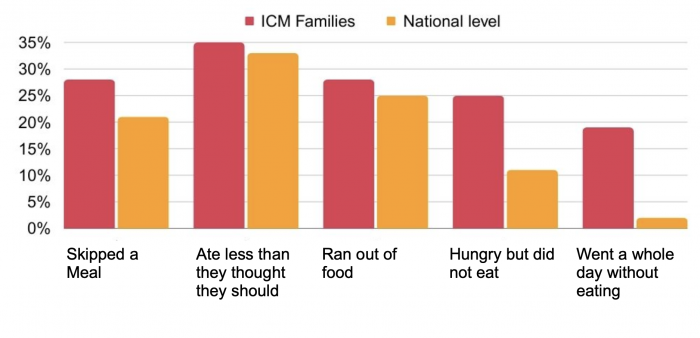

The figures above show the daily realities of ultra-poverty, with hunger being an issue that most families face regularly. Our research shows that 19% of people went a whole day without eating, 28% report running out of food, and more than a third often eat less than they feel they need. It is worth noting that the percentage of ICM participants who reported that they “were hungry but did not eat” was more than twice that of the national figures, and the percent of individuals who “went a whole day without eating,” the most severe indicator, was nearly 10 times the national figure.

The figures above show the daily realities of ultra-poverty, with hunger being an issue that most families face regularly. Our research shows that 19% of people went a whole day without eating, 28% report running out of food, and more than a third often eat less than they feel they need. It is worth noting that the percentage of ICM participants who reported that they “were hungry but did not eat” was more than twice that of the national figures, and the percent of individuals who “went a whole day without eating,” the most severe indicator, was nearly 10 times the national figure.

When we look at the people ICM serves across different provinces of the Philippines, there is a variance in food security between different regions. Across the country, ICM participants have a higher degree of food insecurity than national averages. Families in Leyte, Cebu, Aklan and Capiz face the greatest risks, with 49% of people in Leyte facing hunger, and 36% going a whole day without eating.

Where you live makes a difference

The kinds of communities that ICM families live in across the Philippines also vary greatly. ICM groups communities into roughly five different types: Coastal/Fishing, Mountain, Rural plains, Urban plains, and Urban slum, and a recent research project found significant differences in food security risks according to where families live.

During this project, local enumerators visited households five days a week and asked their start of day cash balance and all the cash outflows for the day. Transactions incurred during the weekend were collected on Monday. For consumption of food items, enumerators asked households to list the items they ate for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks, how much each item cost and whether the item was bought in cash, on credit, or given to the household as a gift.

Food security varied greatly: 94% of households in urban communities in our sample reported skipping a meal compared to only 16% of households in rural communities. Factors that affect how families acquire their goods, such as whether they can grow food, purchase on credit or borrow/receive gifts from neighbors, all impact a family’s food security, and while households in rural areas tend to have less cash, they seem to generally have more opportunities to put food on the table by other means.

Addressing food security for the ultra-poor through training and resources

ICM’s Transform program seeks to address food security in several ways. The first is in the very short-term; we provide every participant of our Transform poverty alleviation program with 18 meals per week, of a soy-rice-vitamin mix that can be cooked in multiple ways. In 2022, ICM distributed US$5.1m worth of food, about 25 million meals, thanks to food partners! Thanks to this partnership, each meal costs just US$0.05 to deliver.

Transform also teaches organic gardening, and gives seeds and vermi (worms to create compost) to participants. For families in urban spaces, we teach how to create container farms, with our “Garden-in-a-Box” kits. As of January 2024, 150,000 families have started a garden, with 2,900 communities working on community gardens. These gardens provide nutritious vegetables, saving families money and providing food for days when there are no other options.

Third, ICM encourages all participants to join community savings groups. Many participants start saving for the very first time after joining Transform. The average savings group has saved US$1,100 after saving together for three years, and members can borrow or withdraw from their group during lean seasons. Although ICM does not have concrete data to link savings group participation to increased food security, it is likely that families with savings to draw on in times can weather lean seasons and not go hungry.

—

Want to help mothers and fathers provide food for their children? Donate here!

–

APPENDIX:

The Household Hunger Survey (HHS), developed by Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance and the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) are validated surveys to measure and compare cross-cultural food insecurity and ability to access food. FIES captures a broader range of food insecurity levels than HHS does, and as such has been adopted for use as the primary tool to measure change in the SDG indicator for Zero Hunger.

Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) Survey

During the last 12 months, was there a time when, because of lack of money or other resources:

- You were worried you would not have enough food to eat?

- You were unable to eat healthy and nutritious food?

- You ate only a few kinds of foods?

- You had to skip a meal?

- You ate less than you thought you should?

- Your household ran out of food?

- You were hungry but did not eat?

- You went without eating for a whole day?

FIES Choices: (Yes / No / I don’t know/ Decline to answer)

Household Hunger Scale (HHS) Survey

- In the past 4 weeks, was there ever no food to eat of any kind in your household because of lack of resources to get food? (Yes / No)

- How often did this happen in the past 4 weeks? (Rarely / Sometimes / Often)

- In the past 4 weeks, did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food? (Yes / No)

- How often did this happen in the past 4 weeks? (Rarely / Sometimes / Often)

- In the past 4 weeks, did you or any household member go a whole day and night without eating at all because there was not enough food? (Yes / No)

- How often did this happen in the past 4 weeks? (Rarely / Sometimes / Often)